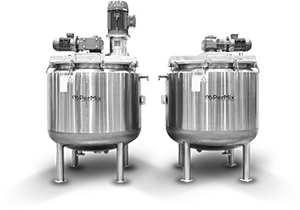

Industrial Mixers

PerMix News & Updates

In today’s advanced powder processing industries — from food and nutraceuticals to battery materials and specialty chemicals — controlling shear inside a plow mixer is critical. Shear directly impacts dispersion, deagglomeration, coating efficiency, liquid incorporation, and final product homogeneity.

But shear in a plow mixer is not a fixed variable. It is adjustable, tunable, and scalable.

Understanding how to control it is what separates commodity mixing from engineered processing.

A plow mixer (also called a ploughshare mixer or fluidized zone mixer) uses high-speed plow-shaped mixing elements mounted on a horizontal shaft. These plows lift and throw material into a mechanically fluidized zone.

Shear is generated through:

The higher the mechanical energy introduced into the bed, the higher the shear rate.

Shear rate refers to how quickly adjacent layers of material move relative to each other. Higher shear rates mean more aggressive particle interaction and faster deagglomeration.

The first and most direct way to control shear in a plow mixer is by adjusting the main shaft RPM.

Higher shaft speeds:

Lower shaft speeds:

Using a variable frequency drive (VFD) allows precise control over shear intensity during different phases of the batch.

For example:

Modern industrial plow mixers allow programmable shear profiles within a single batch cycle.

Choppers (also called intensifier bars) are high-speed auxiliary tools mounted perpendicular to the main shaft.

They create extremely high localized shear zones.

When do you use choppers?

Chopper speed and dwell time determine the degree of deagglomeration. Overuse can create fines. Underuse leaves lumps.

Controlled activation is the key.

Not all plows are created equal.

Shear intensity is influenced by:

Tighter clearances increase particle-wall interaction and raise shear. Wider spacing lowers mechanical stress.

Custom plow configurations are often used in abrasive applications such as:

Material of construction also plays a role — Hardox, stainless steel, or Hastelloy may be selected depending on abrasion and chemical compatibility.

Shear is not just about RPM. It is about how energy distributes through the material bed.

Low fill level:

High fill level:

Controlling batch size is an indirect but powerful shear control method.

Shear dramatically affects how liquids distribute into powders.

High shear:

Low shear:

Spray nozzles combined with controlled shear enable consistent coating and granulation. In advanced systems, atomization pressure and shaft speed are synchronized.

This is particularly important in:

Shear introduces mechanical energy, which can convert to heat.

In temperature-sensitive processes:

For high-temperature applications (including reactive powder processing), shear must be carefully controlled to prevent unwanted phase changes or particle damage.

Shear is cumulative.

Even moderate shear applied over long durations can significantly alter particle size distribution.

Short, controlled bursts of high shear often outperform long, moderate shear cycles.

Batch time optimization is part of shear control strategy.

Poor shear control leads to:

Proper shear engineering results in:

In modern manufacturing — especially in battery materials, nutraceuticals, plant-based proteins, advanced building materials, and specialty chemicals — controlled shear is not optional. It is essential.

Advanced plow mixers are designed with:

Shear is no longer guesswork. It is programmable process control.

And that is what separates blending from true process engineering.

The deeper truth here is that shear is energy. Energy is transformation. When you control energy input, you control matter behavior. And when you control matter behavior, you control product performance.

That’s not just mixing.

That’s physics in motion inside a steel cylinder.

If you’d like, we can now tailor this specifically for:

Each of those industries uses shear very differently — and that’s where this gets really interesting.